The Genetics of Alzheimer's Disease

To understand the genetics of Alzheimer's disease (AD), it helps to start with the basics of genetics. Most cells of the body have 46 chromosomes, grouped into 23 pairs. One chromosome from each pair is inherited from each parent. These chromosomes are composed of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), the genetic material with instructions for how the body grows and functions (See Figure 1). Genes are sections of DNA on the chromosomes. Each gene contains instructions for a specific protein with a specific function. Variations within genes can result in differing traits like hair or eye color. Other variations in gene sequence may cause disease.

Many studies have looked for genes linked to a higher chance of getting AD. They found two types of genes: ones that cause the disease in people with early-onset familial AD, and ones that increase the risk in people with late-onset AD. Early-onset familial AD usually happens before age 65 and often runs in families. But only a small number, less than 5%, of AD cases are like this. Most AD cases are late-onset. People with late-onset AD may or may not have family members with the same condition.

Early-onset Familial Alzheimer's Disease

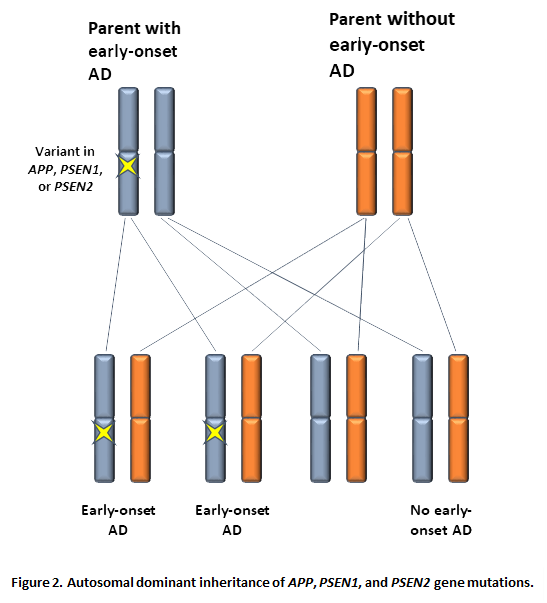

Variants in three different genes have been found in some people with early-onset familial AD. These genes are called amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin 1 (PSEN1), and presenilin 2 (PSEN2). Changes in these genes are passed down in a way called autosomal dominant inheritance (refer to Figure 2). If someone carries a variant in one copy of these genes, they have a 50% chance of passing it on to each of their children. Someone who inherits a mutation in one of these genes is likely to get early-onset AD, usually before age 65 and sometimes as early as 30. But if they don't inherit the variant, they're not expected to develop early-onset AD. They'll still have the same chance of getting late-onset AD as anyone else over 65, which is about 1 in 9 adults. This risk isn't connected to the mutation in the APP, PSEN1, or PSEN2 genes.

Late-onset Alzheimer's Disease

Most people diagnosed with AD start showing symptoms after they turn 65. These cases, called late-onset AD, are usually not caused by changes in the APP, PSEN1, or PSEN2 genes. Instead, it's more likely that a mix of genetic and environmental factors play a role (refer to Figure 3). One gene, called apolipoprotein E (APOE), is a key risk factor for late-onset AD. A specific version of this gene, called APOE ε4, increases the risk of getting AD, but it doesn't mean someone will definitely get AD. That's why APOE is often called a susceptibility gene. It's believed that other genetic or environmental factors are also be needed for someone to develop the disease.

Future Research

Some people with early-onset familial AD don't have changes in the APP, PSEN1, or PSEN2, and some with late-onset AD don't have APOE ε4. This means there must be other genes linked to AD. Research using samples from the National Cell Repository for Alzheimer's Disease will help scientists find these other important genes involved in the risk of developing AD.

Additional Information

For more information regarding the genetics of AD:

- The Alzheimer's Disease Genetics Fact Sheet, Alzheimer’s Disease Education & Referral Center (ADEAR) (http://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers/publication/alzheimers-disease-genetics-fact-sheet)

- Alzheimer Disease, Genetics Home Reference (http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/alzheimer-disease)

- Alzheimer Disease Risk Factors, Alzheimer’s Association (http://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_causes_risk_factors.asp)

- Alzheimer Disease Overview, GeneReviews (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1161/)

- Early-Onset Familial Alzheimer Disease, GeneReviews (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1236/)

The Genetics of Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration

There is growing awareness that dementia can be due different conditions besides Alzheimer's disease (AD). We now see that some of these conditions might have similar causes. Frontotemporal dementia (FTD), semantic dementia (SD), and progressive nonfluent aphasia (PNFA) are due to gradual loss of neurons in the front and/or side parts of the brain. This group of disorders is often called frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD).

To understand the genetics of FTLD, it's helpful to start with the basics of genetics. Most cells in the body contain 46 chromosomes, which come in 23 pairs. We get one member of each pair from each parent. These chromosomes are made up of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), which carries the genetic instructions for how the body grows and works (refer to Figure 1). Genes are sections of DNA found on each chromosome. Each gene holds instructions for a specific protein with a certain job. Changes within genes can lead to differences in traits like hair or eye color. These changes are called variants or mutations. Some variants in gene sequence can cause diseases.

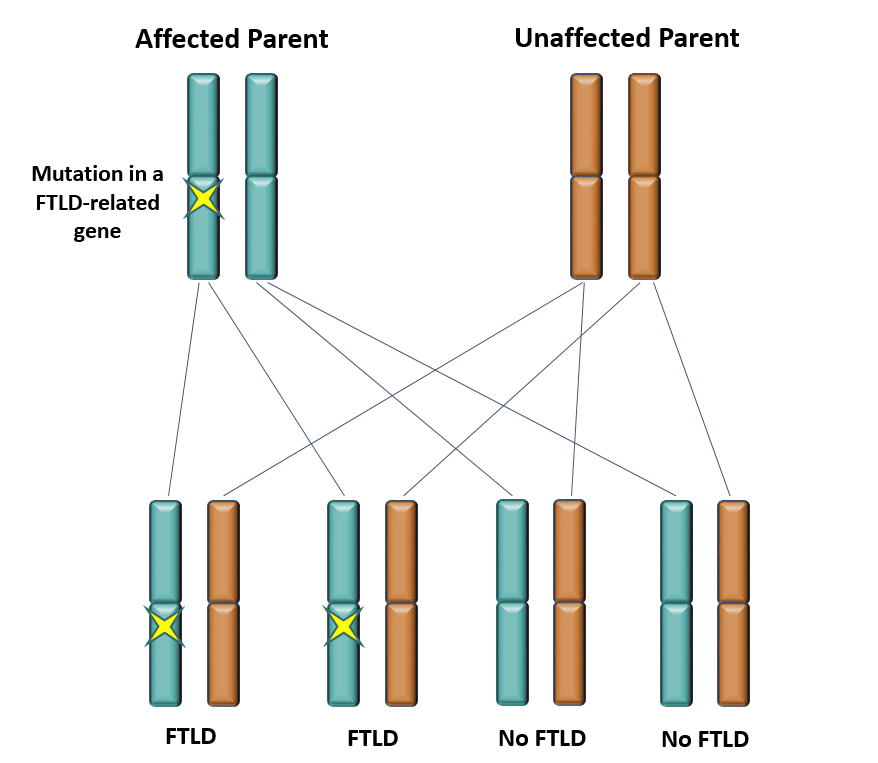

Many studies have looked for genetic variants linked to FTLD. About 40% of FTLD patients have family members with the condition. So far, variants causing familial FTLD have been found in several genes, including microtubule associated protein tau (MAPT), progranulin (GRN), C9orf72, valosin-containing protein (VCP), and charged multivesicular body protein 2B (CHMP2B). The most common genes linked to FTLD are MAPT, GRN, and C9orf72, which likely cause over 80% of familial FTLD cases. Changes in these genes are passed down in a way called autosomal dominant inheritance, meaning a variants in only one copy of the gene is enough for FTLD to develop. If someone carries one copy of a gene variant related to FTLD, they have a 50% chance of passing it on to each of their children. Someone who inherits a variant in one of these genes has a high chance of getting FTLD. But if they don't inherit the mutation, they're not expected to develop FTLD.

Future Research

While many cases of familial FTLD are caused by mutations in the MAPT, GRN, C9orf72, VCP, and CHMP2B genes, others may be the result of changes in genes we haven't found yet. Studies using samples collected and distributed by the National Centralized Repository for Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias will help scientists identify the other important genes contributing to non-AD dementia.

Additional Information

For more information regarding the causes of FTLD:

- Frontotemporal Disorders: Information for Patients, Families, and Caregivers, Alzheimer’s Disease Education & Referral Center (ADEAR)(http://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers/publication/frontotemporal-disorders/basics-frontotemporal-disorders)

- MAPT-Related Disorders, GeneReviews (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1505/)

- GRN-Related Frontotemporal Dementia, GeneReviews (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1371/)

- C9orf72-Related Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Dementia, GeneReviews (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK268647/)

- Frontotemporal Dementia, Chromosome 3-Linked, GeneReviews (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1199/)

- Genetic Home Reference (http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/)

*Riedl L, Mackenzie IR, Forstl H, Kurz A, and Diehl-Schmid J. 2014. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: current perspectives. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment; 10:297-310.