The Brain and Alzheimer's Disease

During the past few decades, a great deal has been learned about the changes that occur in the brain of individuals who have late-onset Alzheimer's disease. While a diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease is often suspected while an individual is alive, the diagnosis can only be confirmed through careful examination of the brain after death.

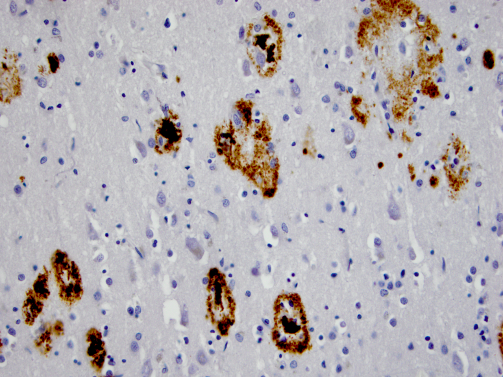

The lack of communication between nerve cells (neurons) is the fundamental cause for the memory loss that is so characteristic of Alzheimer's disease. The two main pathologic abnormalities observed in the brain of patients with Alzheimer's disease are the senile (neuritic) plaques (see figure A) and the neurofibrillary tangles (see figure B). These abnormalities can only be seen with the aid of a microscope.

Courtesy of M.P. Frosch, MD, PhD; Massachusetts Alzheimer Disease Research Center

The core of the amyloid plaques contains a large amount of a protein called beta amyloid. The plaques are located in the space between the cell bodies of neurons. Typically, plaques are located in a part of the brain called the hippocampus, where memories are encoded, and in other regions of the cerebral cortex that are important for thinking and making decisions. The amyloid plaques are dense and do not dissolve. As an individual's disease worsens, the number of plaques increases and their distribution in the brain will often spread.

In contrast to amyloid plaques, which are located outside the neurons, neurofibrillary tangles are found inside the brain cells. In healthy cells, microtubules are involved in the transport of material inside cells. Tau is a protein that works with microtubules in this transport system. In Alzheimer's disease, tau is severely altered and begins to clump together to form tangles. As a consequence, there is an impairment of the transport system that eventually contributes to the death of the cell.

The presence of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles may be found in individuals who did not have any detectable clinical symptoms of Alzheimer's disease during their lifetime. Therefore, it is critical to document the number of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles and where they are located in the brain. Neuropathologists have established several classification systems whereby they can grade the severity of the amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles.

Neuropathology Stains Used

Dementia is a syndrome, a common pattern of signs and symptoms that may be caused by various diseases, sometimes in combination. Many of the specific diseases that cause dementia, such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), are known as neurodegenerative diseases because sets of nerve cells in different brain regions die. With the death of these nerve cells, those regions of the brain stop working properly, thus causing the changes in memory, language, and behavior which mark dementia.

These neurodegenerative diseases may cause the same symptoms because of the brain regions affected even though they have many other differences. For this reason, they are considered as clinico-pathologic entities -- their diagnosis requires both certain clinical (functional) features and certain pathologic (structural) features. Some structural features can be determined by neuroimaging studies like MRI or other methods (“amyloid imaging”); however, the definitive structural changes of dementing diseases require microscopic examination.

Classically, microscopic examination of specific brain regions uses dyes or other chemicals that react with molecules in brain, an area of research called histochemistry. Indeed, more than a 100 years ago Alois Alzheimer used a silver salt to react with tissue to reveal the now famous senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles that are characteristic of the disease that bears his name, and neuropathologists today still use a related method. In addition, they use immunohistochemistry (IHC), a method that stains with antibodies to identify specific proteins or protein modifications in rain. Biochemical and genetic research have highlighted a group of proteins that appear to be central to the specific diseases that cause dementia. Immunohistochemistry is used to probe for these proteins and to highlight the pathologic structures where they are located in brain.

| Protein(s) detected by IHC | Pathologic Structure | Dementing Disease(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Amyloid β-Peptides (Aβ) | Senile Plaques | Alzheimer's Disease [AD] |

| Tau (a Microtubule Associated Protein) | Neurofibrillary tangles | Alzheimer's Disease [AD] |

| Tau (a Microtubule Associated Protein) | Pick Bodies | Pick Disease [PiD] |

| Tau (a Microtubule Associated Protein) | Other Neuronal or Glial aggregates | Frontotemporal Lobar Degenerations [FTLD-tau] (including Corticobasal degeneration [CBD] and Progressive supranuclear palsy [PSP]) |

| α-Synuclein | Lewy Body | Parkinson Disease [PD], Lewy body disease [LBD] |

| α-Synuclein | Glial Cytoplasmic aggregates | Multiple System Atrophy [MSA] |

| TAR DNA binding protein (TDP-43) | Neuronal aggregates | Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration [FTLD-TDP] |

Pathologic Staging of Alzheimer's Disease

Neuritic plaques (NP) of Aβ and neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) of tau are the two hallmark microscopic features of Alzheimer's Disease (AD). Various approaches have been used to assess the patterns of progression of these lesions in the brain and to understand the relationship between them and the emergence of changes in memory and other symptoms of dementia. It is important to understand that Alzheimer’s disease begins many years before the symptoms of dementia appear – examination of the brain can show early findings of the disease when there was no impairment during life.

The most commonly used criteria for evaluating AD are summarized below:

Amyloid distribution (Thal stage)

This approach maps the distribution of deposits of amyloid (Aβ) across the brain. The progression of deposits starts in the neocortex and hippocampus and gradually spreads to deep structures involved in control of movement (striatum) and eventually throughout much of the brain. In general, the more of the brain is involved, the greater the likelihood of impairment.

Braak and Braak Stage

This approach evaluates primarily the distribution of neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) within the brain. There are six stages, from I to VI. These criteria typically are used in the research setting. While we list the usual clinical impression that corresponds to different Braak stages, it is important realize that there many exceptions.

| Stage | NFT Distribution | Typical Clinical Impression |

|---|---|---|

| I/II | entorhinal | Normal cognition |

| III/IV | limbic | Cognitive impairment |

| V/VI | neocortical | Alzheimer’s Disease |

CERAD Score

This approach was proposed by the Consortium to establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s disease (CERAD) and evaluates the density of amyloid deposits that have elicited a specific type of response (neuritic plaques, NP) in specified regions of brain. Neuritic plaques are characterized by the presence of parts of nerve cells which contain inappropriate amounts and forms of tau (the same protein that is present in tangles). The ranking includes sparse (A), intermediate (B), or frequent (C) NP density. The score for NP density is combined with clinical information for a final classification.

NIA-Alzheimer's Association Criteria

This approach, developed in 2012, combines all three of these measures in a single score (“ABC score”, corresponding to the Amyloid, Braak and CERAD scores) to determine the likelihood that a patient would have been demented because of the burden of Alzheimer's disease neuropathologic changes ADNC. It is important to recognize that, once Aβ has been deposited, it is considered that the disease process has begun but that this happens many years in advance of changes in memory or thinking. As the subscores for A, B and C rise (from 0 to 3), it becomes more likely that ADNC are responsible for dementia. Since other diseases might be presented as well (such as changes in the blood vessels or other forms of neurodegenerative disease), some patients will be impaired with lower ABC scores that might be expected. There will be others who, despite having high ABC scores, remain intact without changes in memory or other functions – this is a pattern known as ‘resilience’ and trying to understand it is an important area of research currently.